Robert Indiana has described the 1960s as the most meaningful time of his life. His print portfolio Decade, published by Multiples, Inc., in 1971, commemorated this period with the reproduction of ten paintings made between 1960 and 1969. Included in this exhibition are two serigraphs from the portfolio, Mississippi and The American Dream. In the latter print, based on Indiana’s painting The American Dream I (1961), the artist employs his signature visual vernacular, which he honed over the early part of the 1960s. With its simple geometric configuration, stenciled letters, and flat, bright paint, the work resembles equally a series of fictionalized traffic signs and the hard-edge abstraction made popular by Indiana’s friend and lover Ellsworth Kelly. While Indiana’s work is often characterized in terms of the cool detachment of Pop, the content of American Dream holds personal significance for the artist. US Routes 29, 40, 37 (on which Indiana lived), and the famous 66 figure prominently. The word “tilt” is taken from the pinball games and jukeboxes Indiana encountered in roadside bars and cafes, while “take all” references the naturalized consumerism implicit in the American Dream.1 In this ode to Americana, Indiana speaks to individual nostalgia and to collective experience with his own visual vocabulary.

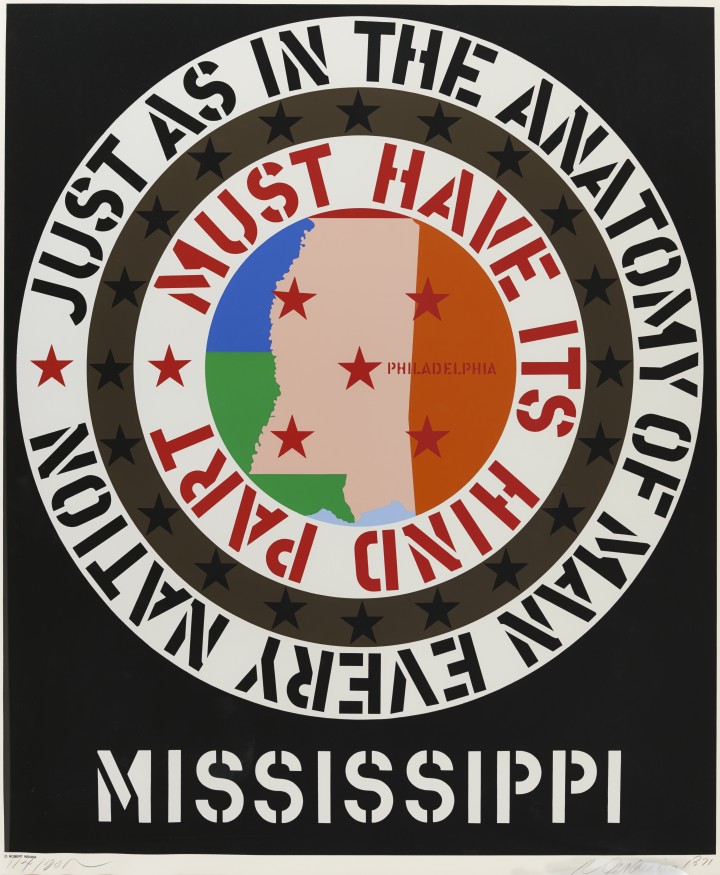

Following a number of separatist movements in the 1960s, the 1970s US saw coalitions of activists with diverse backgrounds working together with the common goal of social change. As a queer artist, Indiana drew a relationship between his own oppression and that of those struggling for civil rights. Mississippi, from Indiana’s 1965-66 Confederacy series, was produced as a response to the 1964 murder of civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. A star on the city of Philadelphia, Mississippi, memorializes the disappearance of the three men, who, following a slew of national media attention, were found to have been murdered by the Ku Klux Klan, with Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey and deputy sheriff Cecil Price charged as one of nine members and conspirators in their murder.

By 1971, Indiana’s iconography had become widely recognizable: bright, flat applications of stenciled uppercase letters, five-pointed stars, circles, squares, and diamonds. In the Confederacy series, including Mississippi, Indiana is verbally explicit about his political critique, incorporating the statement, “just as in the anatomy of man every nation must have its hind part.” Using impactful language—both visual and textual—to draw attention to prejudice, Indiana also draws a relationship between his personal struggle as a gay man and that of a larger community working toward social reform.

1. Robert Indiana, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Artist Questionnaire, December 1961, via http://robertindiana.com/works/letter-form-m/

Robert Indiana Biography

Maddie Phinney Biography