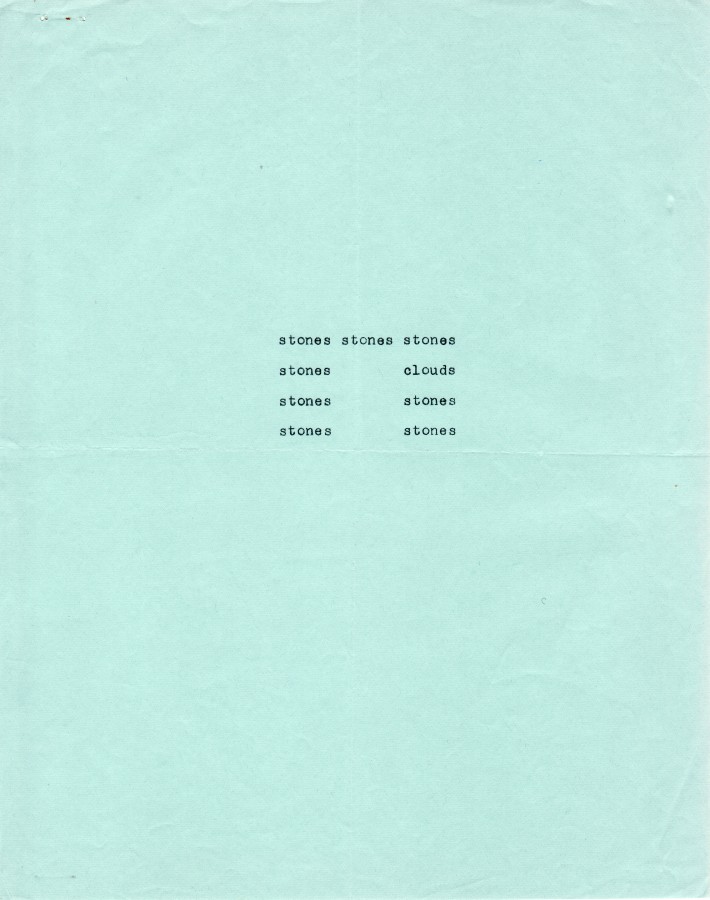

Merging the visual with the textual, concrete poetry presents a coterminous relationship between text and image: reading the words is not sufficient for understanding; one must see the words in order to apprehend the poem. In many cases, were one to read the text aloud the meaning of the poem would be lost. Early forms of concrete poetry used the positioning of words to create visual images, whether simple geometric shapes or objects that reflect the poem’s concepts, such as Ian Hamilton Finlay’s stones stones stones (1966). The positioning of the word stones, eight of them forming a squared arch, and the single word clouds in the upper right corner immediately creates an unmistakable image in our mind: a small garden hut with a window to the sky.

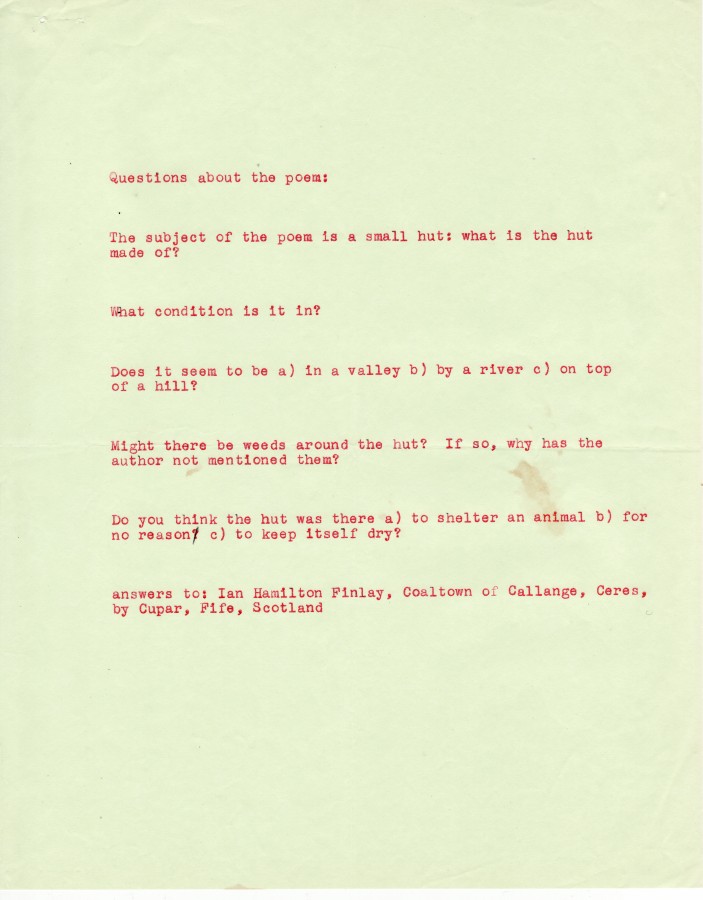

This work illustrates concrete poetry’s investment in the totality of meaning that emerges out of the intersection of word and image. Finlay’s stones stones stones is accompanied in the University at Buffalo’s Poetry Collection archive by a page of questions, inviting reader response and providing his address for the return of replies: “answers to: Ian Hamilton Finlay, Coaltown of Collange, Ceres, by Cupar, Fife, Scotland.” Some questions refer back to the poem’s words, reinforcing the notion that the image and its constituent text are coequal: “The subject of the poem is a small hut: what is the hut made of?” Others invite the reader to contemplate aspects of the work external to its content: “Does it seem to be a) in a valley b) by a river c) on top of a hill?” and “Might there be weeds around the hut? If so, why has the author not mentioned them?” These questions demonstrate that for Finlay, despite his work’s structural emphasis on the image/word relationship, even a concrete poem was not quite as closed to interpretation as one might initially assume.

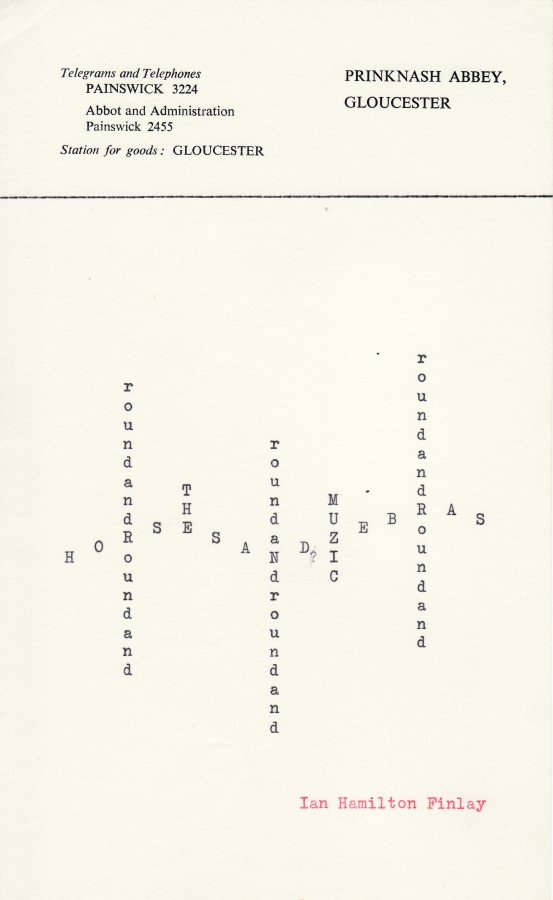

In addition to traditional concrete poems, Finlay experimented with a wide range of other poetic forms, including anagrams, one-line and even one-word poems, and other poetic fragments. In many of these works, he shifted away from an emphasis on the creation of a visual object toward an emphasis on investigating the process of signification and the networks of correspondence that constitute meaning. In these visual poems, the investment is in the variety of meanings available within the work and in the system of relationships across the entire work, as opposed to the relationship between one line or verse and the next, as in more traditional poetic forms. Finlay frequently materializes these relationships by employing a single word read in multiple directions or by pivoting multiple words around a single letter, much like in a crossword puzzle. As they require one to read multiply, these poems make manifest the ways in which such a text – and by extension, all texts – may be opened to multiple meanings. In refusing the hierarchical succession of lines we generally assume in reading, these poems can seem closer to art than text.

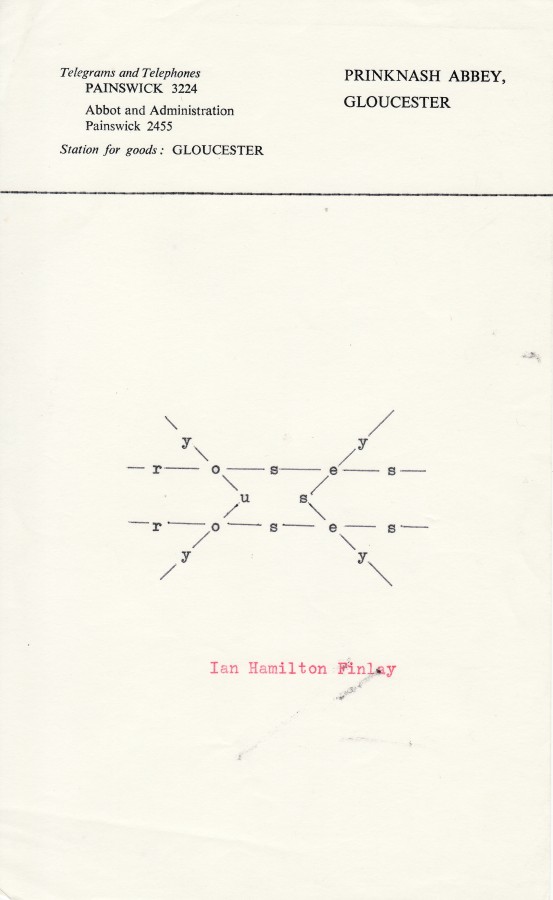

Finlay’s y-o-u y-e-s offers an example. Two iterations of the word -r-o-s-e-s- appear horizontally, while on the left, two instances of the word -y-o-u- traverse the page diagonally, one reading from top to bottom, the other from bottom to top. In a mirrored configuration to the right is the word -y-e-s-. In the space between the two horizontal -r-o-s-e-s- the u from -y-o-u- and the s from -y-e-s- lie adjacent. The o in -y-o-u- is equally the o in -r-o-s-e-s-, while the e in -y-e-s- becomes the e in -r-o-s-e-s-. In addition to the words that are given to us by use of connecting lines, we read between the lines to discover the unconnected us. This unmarked word, emerging from the heart of the work, is the key to its meaning. The unrelated you, roses, and the Molly Bloom-esque yes all coalesce around us, clearly marking this as a love poem.

Such decentering of authorial control and focus on networks of correspondence allow each reader to determine their individual experience of the poem. In Finlay’s y-o-u y-e-s, rather than following the traditionally prescribed left-to-right, top-to-bottom flow, the reader can choose which line to read first and how to travel through the poem. Reading the poem puts the reader in the position of contravening the conventional rules of reading, which awakens the awareness that alternatives are possible. This awareness lies at the heart of the work’s political potential. When we are able to recognize that it is possible to read against conventional norms, we realize that other norms may be similarly challenged, other rules similarly breached, and it becomes possible for us to imagine other relationships with power.

Ian Hamilton Finlay Biography

Sarah JM Kolberg Biography

Pingback: Sarah JM Kolberg on Dom Sylvester Houédard