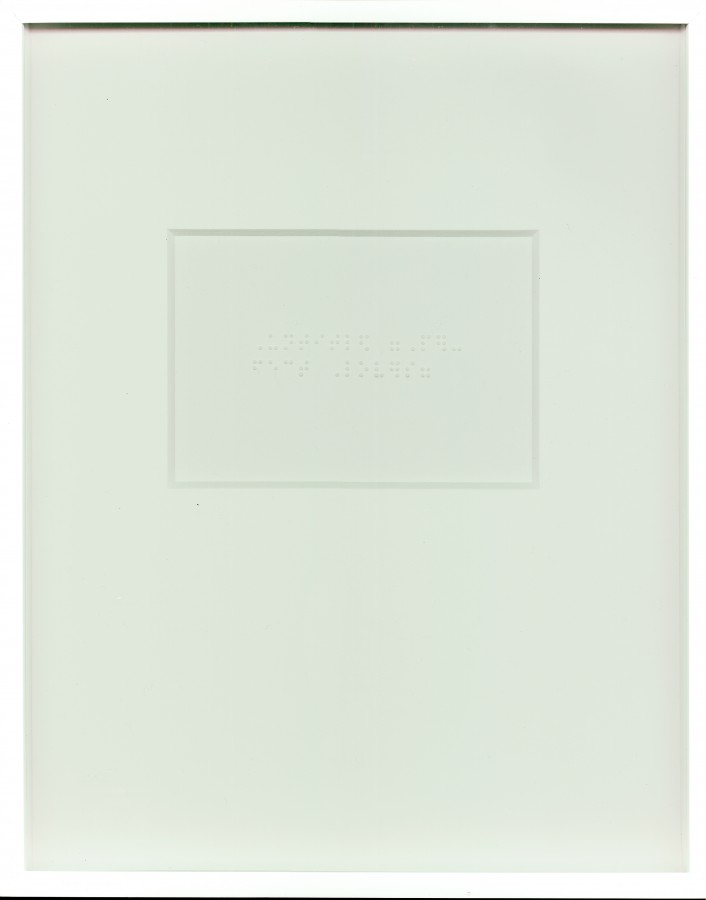

Each artwork in Richard Bassett’s Art Titles series was made using a standard Braillewriter and reproduces in Braille the title of another artist’s work, such as Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing, Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait, and, in the case of the work shown in this exhibition, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers) (1987-1990). In order to make this series, Bassett frequented his local Braille academy and interviewed staff and students to learn about Braille’s stylistic conventions and production methods. A Braillewriter is akin to a manual typewriter but has only six keys—one for each of the six possible positions that make up the Braille system, and three function keys: a line return, a space key, and a backspace key. Using a paper template with blank dots arranged in the six positions, Bassett carefully translated onto the template the words and punctuation that he wanted to reproduce in Braille. Once proper layouts of the source text were determined, Bassett typed with the Braillewriter onto a piece of heavy embossing paper, creating an object in relief.

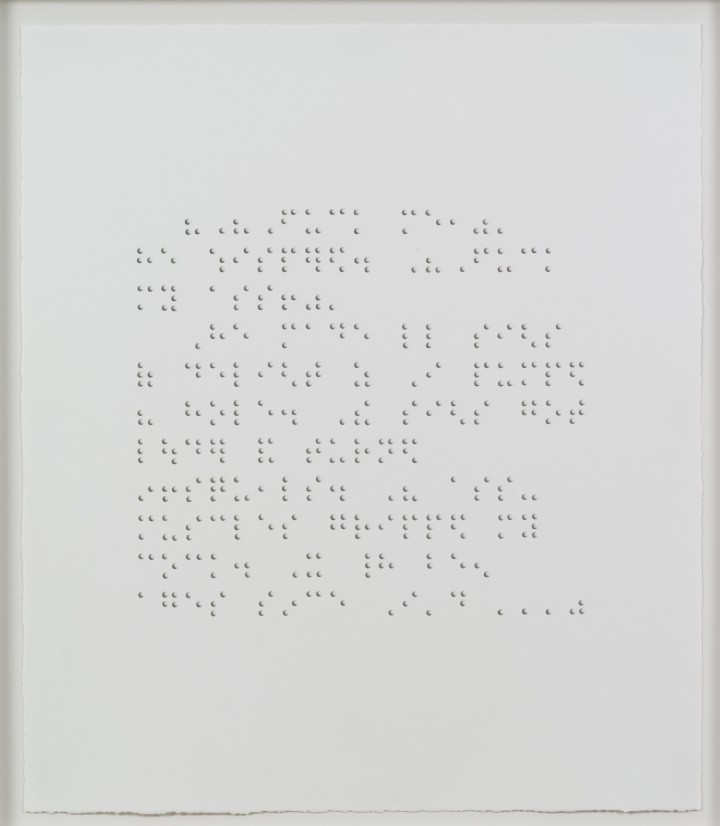

Although learning to work with the Braillewriter delighted Bassett, according to his partner, Donald Bradford, the artist felt that simply typing Braille was too easy. He relished the technical challenge of reproducing realistic Braille through drawing. One of a series of approximately two dozen works drawn by hand rather than typed with a Braillewriter, Porn Clip #5 (1999) is based on a passage from the erotic short story “Night Bus to Reno,” which was published in the December 1990 issue of the gay porn magazine Inches. Bassett selected roughly a paragraph of text, translated it into Braille, and painstakingly rendered the Braille with graphite in hyperrealist style. According to Bradford, Bassett chose stories and passages based on his fantasies. This particular story involves a protagonist named Richard, a young soldier on leave who experiences his first gay sexual encounter. As Bradford recalls, Bassett was amused by the fact that his own work’s lewd and graphic depiction of this encounter hides in plain sight—visible but not legible—and subversively introduces an illicit element into the rarefied air of the gallery.

In selecting methods that yield text legible only to some, Bassett plays with the dialectics of optics, which here become a metaphor for the negotiation between visibility and invisibility in homosexuality. Porn Clip #5 is a visual paradox: an accurate translation that might be legible to a sighted person with knowledge of Braille, but which is frustratingly illegible to the blind because the marks are drawn, not embossed. This illegibility speaks to the inadequacy of both language and art to convey authentic experience, an inadequacy that was at the heart of many Cold War-era artists’ rejection of Abstract Expressionism’s gestural mark. Gesture was understood as the visual trace of the artist’s presence, phenomenologically linked to the body that produced it. Jasper Johns and Robert Indiana relied on stencils to expose the fraudulence inherent in the idea of gestural authenticity, demonstrating that the appearance of the gesturally authentic can be manufactured and reproduced. Bassett performs a similar negation, reducing an intimate physical experience to a series of regulated dots in a grid. And while Porn Clip #5 initially promises a return to the phenomenological in evoking Braille’s tactility, this return is frustrated by its two-dimensional surface. This twinned negation functions to sever the work’s formal qualities from its socio-historical meaning.

Bassett uses the theme of invisibility in his work to political effect, as did his subject Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Untitled (Perfect Lovers), the piece by Gonzalez-Torres that Bassett references in this work from the Art Titles series, was made in tribute to Gonzalez-Torres’s lover, Ross Laycock, as so many of his works were. It consists of two identical battery-operated commercial office wall-clocks, such as might be seen on a news bureau wall, hung side by side, their casings touching. At the time of installation the clocks are synchronized, but as the batteries run down, they eventually drift out of synch and stop. The clocks can be read as a metaphor about the synchronization between lovers, a notion supported by a letter Gonzalez-Torres wrote to Laycock in 1988, in which he wrote, “we are synchronized, now and forever,” and at the top of which he drew two synchronized clock-faces.1 But the clocks’ eventual slowing and stopping would also come to metaphorize the couple’s literal de-synchronization as a result of Laycock’s death from AIDS in 1991, preceding by five years Gonzalez-Torres’s own AIDS-related death.

As a gay Cuban man with AIDS, Gonzalez-Torres inhabited three minoritized identity categories, yet reference to and representation of these identifications is notably absent in his work. His titling convention further distances the work from any self-identificatory signification. Nearly all of his works are titled Untitled, followed by a parenthetical referent “suggesting a meaning related to experiences of the artist’s life, but always open and multivalent,”2 allowing the titles to be both personal and widely inclusive of his audience. José Muñoz argues that Gonzalez-Torres employs a strategy of “disidentification,” which Muñoz describes as “the survival strategies the minority subject practices in order to negotiate a phobic majoritarian public sphere that continuously elides or punishes the existence of subjects who do not conform to the phantasm of normative citizenship.”3

Gonzalez-Torres was openly queer, and his HIV-positive status was a well-known subject of his work. His avoidance of these identifications in his art was not a self-protective move, as were the self-distancing strategies of this exhibition’s Cold War-era homosexual artists. Rather, he intended to short-circuit a conservative American museum culture that had refused to address AIDS, in part to avoid drawing fire from a resurgent religious right intent on policing the art world and erasing all representations of both homosexuality and AIDS. With an increasingly bellicose political right in Congress willing to serve as the religious right’s handmaiden, the stakes were clear, as exemplified by the Corcoran Museum of Art’s pre-emptive cancellation of a 1989 Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective in order to avoid the loss of public funding. Gonzalez-Torres’s rejection of these discursive terms was thus a way to produce art fully informed by his status as an HIV-positive gay man, but not explicitly so. His work functioned as a “virus” within the museum world, a term he used advisedly: capable of seeding dissident meanings without being visible as itself dissident. This dialectic would become a central thematic in Richard Bassett’s work as well. That these investigations take place in the culturally symbolic space of the art gallery only brings into sharper relief their metaphoric reminder of how thoroughly homosexuality has been excluded from and rendered invisible within the public realm.

1. Julie Ault, Félix González-Torres (Göttingen: SteidlDangin, 2006), 155.

2. Monica Amor, “Félix González-Torres: Towards a Postmodern Sublimity” Third Text 30 (1995): 73.

3. José Muñoz, Disidentification (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 4.

Richard Bassett Biography

Sarah JM Kolberg Biography