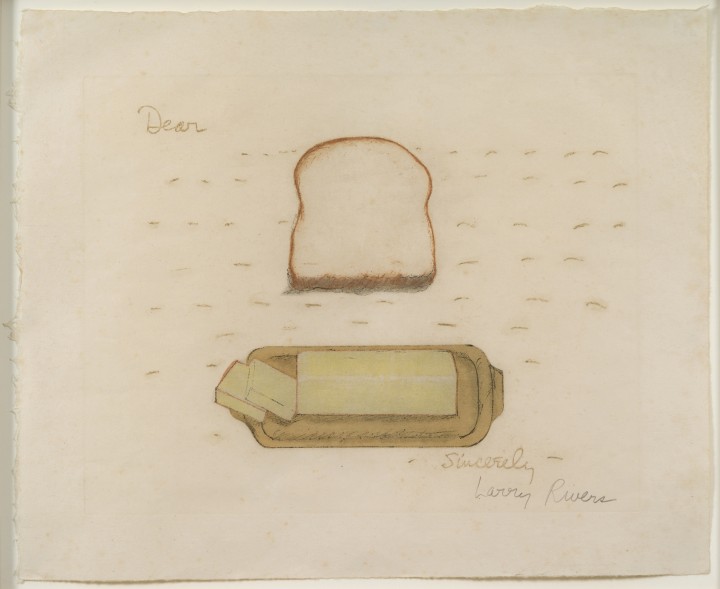

Larry Rivers’s etching and screenprint Bread and Butter (1974) takes the form of a letter, with the obligatory “Dear” and “Sincerely” bracketing a slice of bread, a stick of butter, and the dotted line that we conventionally associate with missing words. The term “bread-and-butter letter” is a colloquial expression, now largely fading, for a thank-you note sent in return for hospitality—something that’s done as a matter of course, like putting butter on your bread. The words bread and butter together evoke the quotidian, but the image Rivers presents is anything but. A kind of rebus, but a performatively incomplete one, it enfolds images into, or more precisely onto, an epistolary format that irritates our desire for narrative closure. While we can read the image, we can’t really understand it, and we cannot attribute any definitive meaning to it beyond its curious literalization of an old-fashioned phrase.

But Bread and Butter is theoretically sophisticated beneath its Pop surface. If a bread-and-butter letter is a requisite social nicety, then in some sense what that letter declares is less significant than the fact of its delivery. Rivers’s image thus asks whether a bread-and-butter letter that merely illustrates the bread and the butter sufficiently functions to fulfill this social duty. In this sense, Rivers’s print is a latter-day meditation on Jasper Johns’s iconic flag painting, which similarly asks whether a painting of an American flag is ontologically akin to an authentic flag, provided that it, too, presents the requisite red, white, and blue palette in the appropriate design.

Rivers’s larger career has tended to fall outside the usual frames for understanding the development of American art. He was a contemporary of the Abstract Expressionists but is more commonly regarded as part of a succeeding generation of Pop artists—this despite the fact that his first ostensibly Pop paintings date from the early ‘50s, a decade before Pop’s emergence. Rivers falls out of the frame stylistically, too, in that his work, especially early on, combined an Abstract Expressionist gestural brushiness with a realism so convincing it seemed to belong to another time. Rivers mingled two modes that were considered mortal enemies, a shotgun wedding through which he suggested that style was merely a means to an end—rather than the end itself, as it was then understood. Finally, Rivers parted company with his confederates in Abstract Expressionism by cultivating the ironic, jokey, dexterous patois of the largely gay circle surrounding his great friend and sometime lover Frank O’Hara.

O’Hara and Rivers were responsible for one of the great satires ever produced about Abstract Expressionism, particularly notable for having been written when the movement was in its prime. Their shared authorship of “How to Proceed in the Arts,” subtitled in mock seriousness, “A Detailed Study of the Creative Act,” resulted in a kind of post-Abstract Expressionist manifesto. Its repeated assaults on Abstract Expressionism from, as it were, within—the glib references to favorite buzz words, the undercutting of sacred tropes—served notice that what was once beleaguered had become the establishment. O’Hara and Rivers’s no-holds-barred satire took many of the most sacred precepts of Abstract Expressionism to task, such as the notion that if one is painting “in the moment,” then the picture should come forth holistically and spontaneously, and not as a matter of forethought, design, or calculation. Titled and conceived as a primer for avant-garde success, the article bears quoting in detail:

7. They say your walls should look no different than your work, but that is only a feeble prediction of the future. We know the ego is the true maker of history, and if it isn’t, it should be no concern of yours.

8. They say painting is action. We say remember your enemies and nurse the smallest insult….Be ready to admit that jealousy moves you more than art. They say action is painting. Well, it isn’t, and we all know Expressionism has moved to the suburbs.

9. If you are interested in schools, choose a school that is interested in you. Piero Della Francesca agrees with us when he says, “Schools are for fools.” We are too embarrassed to decide on the proper approach. However, this much we have observed: good or bad schools are insurance companies. Enter their offices and you are certain of a position….

13. Youth wants to burn the museums. We are in them–now what?…Embrace the Bourgeoisie. One hundred years of grinding our teeth have made us tired. How are we to fill the large empty canvas at the end of the large empty loft? You do have a loft, don’t you, man?

14. …We’re telling you to begin. Begin! Begin anywhere. Perhaps somewhere in the throat of your loud ass hole of a mother? O.K.? How about some red-orange globs mashed into your teacher’s daily and unbearable condescension. Try something that pricks the air out of a few popular semantic balloons; groping, essence, pure painting, flat, catalyst, crumb, and how do you feel about titles like “Innscape,” “Norway Nights and Suburbs,” “No. 188, 1959,” “Hey Mama Baby,” “Mondula,” or “Still Life with Nose”? Even it is a small painting, say six feet by nine feet, it is a start. If it is only as big as a postage stamp, call it a collage–but begin.1

In the face of the bombastic Sturm und Drang of ‘50s Abstract Expressionism, Rivers’s work was instead overtly domestic, featuring a rotating cast of his own family members, including his mother-in-law, Birdie, often depicted in the nude. Manifestly character studies, these domestic scenarios were joined by other works that ironized or undercut a great deal of the high seriousness of the art world at that time. For instance, many of the leading Abstract Expressionist artists gathered at a dive bar called the Cedar Tavern, where they drank heavily, fought often, and generally behaved rather differently from most assumptions regarding the private lives of those refined aesthetes we term artists. Rivers, in turn, made a painting called Cedar Bar Menu that punctured the mythic aura surrounding the tavern, pointing to the cheesy menu and, by extension, to the run-down, even squalid circumstances that obtained there.

By the late ‘50s, the deployment of text was a regular part of Rivers’s work, and such painting series as Lions on the Dreyfus Fund, or one comprising variations on the Camel cigarette package, underscored the inseparability of text within his art. Some paintings were even labeled as vocabulary lessons, offering the names for various parts of the human anatomy in, say, French, along with arrows pointing to the proper place on a nude figure. But the apogee of his work with language is arguably Stones, a lithographic series completed with Frank O’Hara, in which O’Hara’s poetry and Rivers’s imagery resonate in complex ways. Text began to play an even more significant role in a later series of highly politicized works that followed early clashes over the Civil Rights movement. For example, he made a painting with a black penis, a white penis, and a ruler—all of the same length—with text reading America’s No 1 Problem.

By the time he completed Bread and Butter, Rivers was viewed most centrally as a Pop artist, and the work betrays a Pop sensibility. But unlike other Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Rivers’s hand is always evident in his work—a gestural holdover from and a tribute to his complicated relationship with Abstract Expressionism.

1. Frank O’Hara and Larry Rivers, “How to Proceed in the Arts,” Frank O’Hara Art Chronicles 1954-66:93, originally in Evergreen Review V, 19 (August 1961).

Larry Rivers Biography