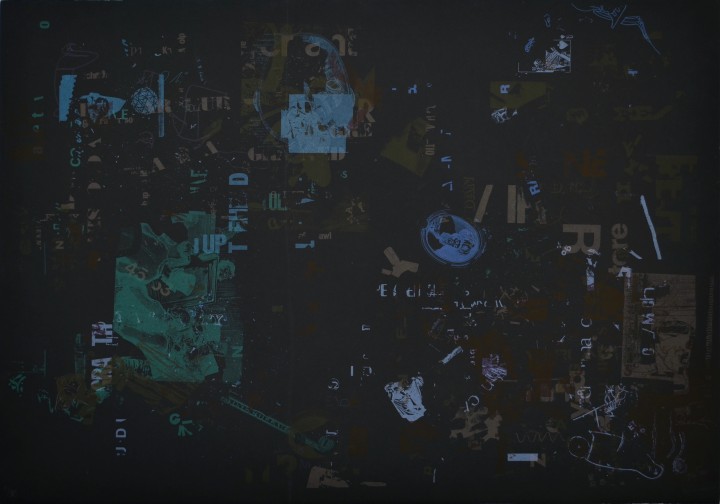

The work shown here is just one element of John Cage’s Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel (1969), a series of compositions comprising eight Plexigrams—each itself eight sheets of silk-screened Plexiglas, mounted in a slotted wooden base and accompanied by one of two different lithographs. Fragments of words, letters, and images are scattered across the surface of each component, as seen the lithograph on view here. Depending on the viewer’s angle before the assembled work, aspects of each pane line up with or fall away from those on other panes. Not only does each viewer’s experience of the work differ, but one individual viewer can have multiple experiences of the work depending on the angle of view, a metaphor as much about politics as it is about art.

Created by Cage as a memorial to fellow artist and friend Marcel Duchamp, Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel echoes Cage’s practice of mobilizing silence in his musical compositions to erase the typical power relationship between artist and viewer. By allowing silence to enter the performance, Cage brings the unique circumstances of each listening context into play, thereby letting sounds he cannot control supersede those he can. For Cage and his fellow homosexual artists, silence served another crucial function: as a form of covert resistance to the dominant culture’s totalizing control. Recognizing that any actions perceived as openly oppositional would only elicit further repressive impositions of power, Cage and his cohort developed strategies, like silence, that allowed forms of camouflaged dissent, evading control by not being openly resistant.

As Cold War-era homosexuals learned to disguise their authentic selves behind a publicly acceptable front of heteronormativity, a less pernicious form of this self-silencing strategy was being adopted by legions of “men in grey flannel suits.” As William H. Whyte’s best-selling book of the era The Organization Man explores, the code of conformity imposed on American life in the ‘50s, particularly in corporate culture, necessitated if not actual conformity, then at least the outward appearance of it. Corporate workers quickly learned that to get ahead they must cultivate a carefully crafted public self that might be quite different from one’s more authentic private self. As a result, Jonathan D. Katz argues, heteronormative America was being similarly trained in the value of the closet as a mode of survival.1

The Cold War politics of selfhood demanded a practice of not saying. In the opening of his 1949 essay “Lecture on Nothing,” Cage writes, “I am here, and there is nothing to say,” and then, in typical Cageian fashion, continues for 575 more lines. His point, however, is not that there is literally nothing to say, but rather that he wants to draw our attention to the dynamics of power inherent in language and, in relinquishing this power, to transfer agency for meaning-making to the reader. At the heart of Cage’s aesthetic is a deeply ethical political project. In refusing the normal majority/minority operative binaries, Cage erases the prevailing hierarchical dialectic of power, creating the possibility of multiple and shifting hierarchies. Elsewhere, Cage speaks against communication, in favor of conversation. Communication entails a unidirectional flow of ideas, a message to be conveyed and received, as opposed to conversation, which allows for the free exchange of ideas. Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel is a conversation with the viewer, who creates meaning from the various word and image fragments Cage has provided.

Cage frequently used chance operations in creating his works in order to eliminate his personal tastes, which he saw as necessarily delimited by what he already knew. Here the placement of words and images, their size, and their color were determined by the I Ching, an ancient Chinese chance-based system of divination. Devoid of any specific focus or narrative, the resulting surface invites the viewer’s eye to wander, taking in word and image fragments and reworking them in endless combinations. In this way Cage silences his own voice and allows the viewer to complete the work. In the context of the Cold War, the notion of individual freedom was a conservative fundamental idea, one that ideologically differentiated us from the Soviet Union’s forced collectivity. By offering the viewer freedom to make meaning, Cage deftly camouflages his radical freedom in the terms of America’s most fundamental claim about itself.

Whether in his musical or visual compositions, Cage created opportunities for the production of a new form of subjectivity, one in which the viewer is not merely a consumer, but an active producer of meaning. This is the element that gives these works such subversive power. Cage enables viewers to perceive themselves and their relation to power in new ways and, in imagining these new relations, to discover new means of eluding power’s control. As is often the case with Cage, not saying anything at all said more than saying something in the first place, since the absence of statement forced the audience to embrace the freedom to make meanings on their own. As he wrote, “I have nothing to say, and I’m saying it.”

1. Jonathan D. Katz, “Passive Resistance: On the Success of Queer Artists in Cold War American Art” L’image 3 (December 1996): 119-142.

John Cage Biography

Sarah JM Kolberg Biography