Audio Transcript

Translation across media is notoriously ineffective, and when I sat down to write about Mary McDonnell’s Untitled (2007), my frustration and poor results exemplified that difficulty. The idioms lost between image and text are no different from untranslatable figures of speech. Some art begs to be explained, written about, and encased in academic language (conceptual art comes to mind), but McDonnell’s work demands to be experienced.

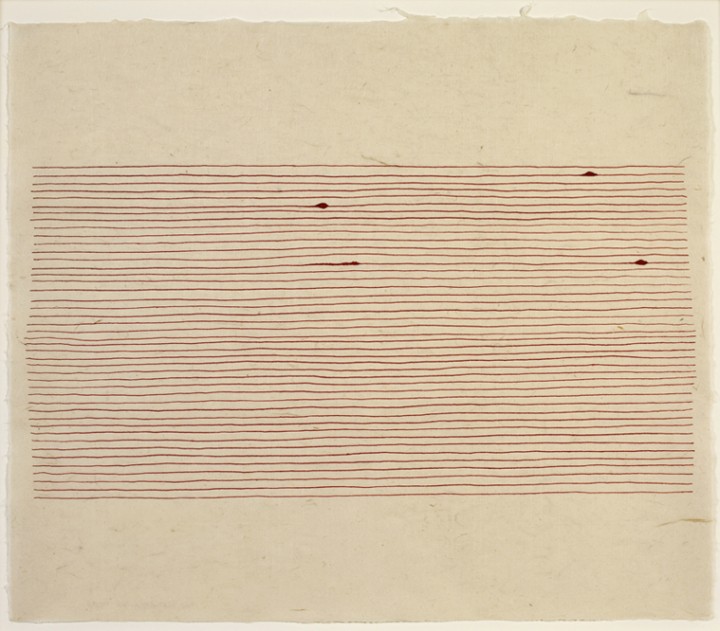

Both McDonnell’s paintings and drawings preserve and present their creation, acting simultaneously as objects and archival records. Yet the particular invitation of the works on paper in the “Red Line Drawings” series is situated in their mechanical familiarity. (Who has not drawn a line in pen on paper?) Acquaintance with this action increases our appreciation of McDonnell’s skill—forty-four lines, remarkably straight—as well as our understanding of what she calls “incidents” in the process: the inevitable blotches and bleeds of ink. Thus, during sustained viewing the character of Untitled vacillates between approachable and aloof: the intimate scale draws us in, but the fine art context places it just beyond reach; the familiar action recalls a commonplace experience, but the artist’s dexterity repositions it on the authoritative gallery wall. It is in this vacillating, this trembling—echoing the human trembling of the lines—that the complexity of this deceptively simple work is revealed.

McDonnell started these works when she was experiencing artistic frustration while on a residency at The MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. In an attempt to still her mind and enter a meditative place she started drawing lines on a piece of paper whose handmade quality had captivated her. One page a day, for several days, the lines proceeded without disturbance. When the first blotch arrived, McDonnell paused before accepting it as a necessity of the process, and then, as she described to me, “that was that.”1 The final number of drawings in the series is around fifty (she is unsure of the exact quantity), and they record McDonnell overcoming a passage of unproductivity through dedication, practice, and repetition. As physical documentation of her mental discipline they connote a schoolchild’s written lines or a monk’s manuscripts. Additionally, the solution to McDonnell’s struggle was also a beginning: besides representing a completed task the artwork resembles the grid of blank sheet music facing a composer, pregnant with possibility.2 The inherent potential of these lines effectively soothed the artist’s frustration, impelling her to bring that mentality back to her studio and subsequent work.

While the artist is undoubtedly skilled, her work proceeds from subjective intuition more than from premeditated technical consideration. “[From] the gut,” she explains, while embedding her fingers in her abdomen. Everything about this series of works could be construed as accidental: the number and placement of the lines, the irregular incidents, even the color of the ink (red was the color McDonnell happened to have the first day she began). Yet these characteristics are only “accidental” in the sense of being unplanned. They arise from the intuition of an artist who has spent her career considering color and form, who stripped these works down to reveal the fundamental tenets behind her more visually complex works: expressive line, lyrical movement, evocative color, careful positioning. In this sense the intuition that McDonnell heeds is both an inexplicable prompting and the automatic response of learned mastery.

The generative practices that led to Untitled reflect McDonnell’s broader creative habits. Beyond facilitating the visceral composition of each piece, the artist has situated herself in and towards life in a posture of attentiveness. In her upstate New York studio she paints amid the “silence” of nature, which she has discovered contains a polyphony of birds and running water. She lives with paintings for months, until she perceives the stirring that reveals how finally to fulfill them. Simone Weil wrote that true prayer is an attitude of attentiveness,3 but McDonnell is more of a midwife than a worshipper. The monolithic “act of creation” really comprises a series of acts, continual preparation for the awaited delivery.

1. All facts about the genesis of this piece, details about the habits of McDonnell’s practice, and record of her words are from an interview she graciously granted the author (23 June 2011).

2. McDonnell has a musical background, and her work’s affinities with music are not tangential. Multiple composers, including Meredith Monk, Linda Dusman, and Fred Hersch, have responded to her art in their own medium, continuing the cross-disciplinary trend.

3. Simone Weil, “Waiting for God” in Waiting for God (New York: Harper Perennial, 2002), 57-58.

Mary McDonnell Biography